Because of color choices, there is often a lot of confustion on websites. Your eyes dart across the screen, unsure of where to look first. Nothing stands out, and everything seems to be competing for your attention. This common experience is a failure of design, specifically a failure to establish a clear visual hierarchy. It is a digital space without a roadmap.

Now, imagine an interface where your eyes are effortlessly guided from the main headline to the supporting text, and finally to the one button you are meant to click. This intuitive journey is the direct result of a well-executed visual hierarchy. While many tools like font size and spacing contribute to this, one of the most powerful and nuanced is font color.

This brings us to our central argument: Font color is not merely an aesthetic choice or a decorative flourish. It is a primary architectural tool for constructing a clear visual hierarchy. When used with intention and understanding, color guides a user’s eye, signals the importance of information, creates relationships between elements, and fundamentally shapes the entire user experience.

In this definitive guide, we will deconstruct the mechanics of color’s profound influence on visual hierarchy. We will begin with the foundational principles of color itself, explore the science of how we perceive it to create order, and delve into the psychology of how color communicates meaning. Finally, we will cover the non-negotiable mandate of accessibility and provide a practical framework to master font color in your own designs, transforming confusing layouts into models of clarity and purpose.

1. Foundational Concepts: Defining the Core Components

Before we can effectively use color to build a visual hierarchy, we must first agree on our terms. Understanding the core components of both visual hierarchy and color is the essential first step toward mastery. Without this foundation, any design choices are simply guesswork.

What is Visual Hierarchy?

At its simplest, visual hierarchy is the principle of arranging elements on a page to show their order of importance. Our brains are wired to look for patterns and shortcuts. When we see a page of information, we do not read it like a book, word for word, line by line. Instead, we scan for visual cues that tell us what is most important, what is secondary, and what we can safely ignore if we are in a hurry. A strong visual hierarchy provides these cues intentionally. It is the silent guide that tells a visitor, “Start here, then look at this, and if you are interested, here is some more detail.”

Think of a newspaper. The giant headline is the first thing you see. It has the highest position in the visual hierarchy. The smaller subheadings are next, followed by the main body of text. Photo captions and other minor details are designed to be the least prominent. This clear structure is a classic example of visual hierarchy at work. In digital design, we use these same principles to control the user’s journey and make interfaces easier to navigate and understand. A successful visual hierarchy reduces confusion, increases usability, and helps users achieve their goals more efficiently. Every decision we make about color directly impacts this delicate structure.

What Governs Font Color’s Impact?

When we talk about “color,” we are often simplifying a more complex reality. To use color effectively in our pursuit of visual hierarchy, we need to understand its three distinct properties. These are Hue, Saturation, and Luminance. Many designers, especially those starting out, focus almost exclusively on hue, but the other two properties are arguably more important for creating a functional visual hierarchy.

- Hue: This is the purest form of the color, the quality that gives it its name in the rainbow. Red, green, blue, yellow, and orange are all hues. It is the most basic property of color and what we typically think of first. While hue is great for branding and creating a specific mood, it is the weakest tool of the three for building a reliable visual hierarchy on its own.

- Saturation: This refers to the intensity or purity of a hue. A highly saturated color is rich, vibrant, and vivid. A color with low saturation is more subtle, muted, and closer to gray. Think of turning up the color setting on your television. A bright, fire-engine red is highly saturated, while a dusty, faded brick red has low saturation. Saturation is excellent for drawing attention. A single, saturated element in an otherwise muted design will immediately jump to the top of the visual hierarchy.

- Luminance (or Value): This is the most critical property for establishing a clear visual hierarchy. Luminance is simply how light or dark a color is, on a scale from pure white to pure black. For example, a light baby blue and a dark navy blue can have the same hue (blue) but vastly different luminance values. Our eyes are extremely sensitive to changes in luminance, which is why the contrast between a color’s brightness and its background is the number one factor in determining how legible text is. Mastering luminance is the key to creating a design that is both readable and well-structured, forming the backbone of a successful visual hierarchy.

2. The Science of Seeing: How Color Contrast Creates Order

Our ability to perceive visual hierarchy is rooted in the biology of our eyes. We do not see all visual information equally. Our visual system is highly optimized to detect differences, and the most significant difference it is built to detect is contrast. In design, contrast is simply the difference between two elements. When it comes to font color, this primarily means the contrast between the text and the background it sits on. This is where we leverage luminance to build an effective visual hierarchy.

Luminance Contrast: The Primary Driver of Hierarchy

As mentioned, the human eye is far more sensitive to luminance contrast than it is to differences in hue. This is because the part of our eye responsible for seeing in low light and detecting brightness (the rods) is highly sensitive. When the luminance difference between text and its background is high, the text is easy to read and stands out. When the difference is low, our eyes have to work harder, and the text recedes in importance. We can use this to our advantage to create distinct levels in our visual hierarchy.

- High Contrast for Primary Information: For the most important text on a page, like the main body copy, you need maximum readability. The classic example of this is black text on a white background. The luminance difference is at its maximum, making the text effortless to read for long periods. This high contrast immediately signals to the user that this is foundational content. It firmly places this text at a specific, readable level of the visual hierarchy.

- Medium Contrast for Secondary Information: Not all text is created equal. Information like dates, author names, or descriptive captions is important but secondary to the main content. For this text, you can use a color with medium contrast. For instance, on a white background, instead of using pure black, you might use a medium gray. This subtle shift in luminance is instantly perceived by the brain. It communicates that this information is less critical than the main body text, creating another clear step in the visual hierarchy without causing readability issues.

- Low Contrast for Tertiary or Inactive Elements: Sometimes, you need to display information that is not essential or is in an inactive state, like a disabled button or a copyright notice in a footer. In these cases, a very low luminance contrast is appropriate. A light gray text on a white background, for example, is still readable upon close inspection but fades into the background during a casual scan. This effectively pushes it to the bottom of the visual hierarchy, ensuring it does not compete with more important elements.

Chromatic Contrast: Using Hue and Saturation Strategically

While luminance does the heavy lifting for readability and structure, contrast of hue and saturation is your tool for drawing immediate attention to specific elements. Our eyes are also drawn to things that are different from their surroundings. This is a survival trait; we are programmed to notice the single red berry in a green bush. We can use this principle, often called the Isolation Effect, to guide the user’s focus.

A highly saturated color, especially a warm hue like red or orange, will appear to advance, or come forward, in a design. Cooler, less saturated colors, like a muted blue or gray, will appear to recede. By placing a single, vibrant, and saturated color in a design that is otherwise calm and muted, you can instantly make that element the most important thing on the screen.

This is the perfect technique for Call-to-Action (CTA) buttons, error notifications, or important alerts. You are using color not just to organize the page, but to tell the user, “Look here! This is what you need to do next.” This strategic use of hue and saturation adds a dynamic, action-oriented layer to the foundational structure created by your luminance contrast, completing a sophisticated visual hierarchy.

3. The Psychology of Color: Assigning Meaning and Function

Beyond the purely physical act of seeing contrast, color also has a powerful psychological dimension. We have been conditioned throughout our lives to associate certain colors with specific meanings and functions. A designer who understands this can use color to communicate complex ideas instantly, reducing the mental effort required from the user. This layer of meaning is a crucial component of an effective visual hierarchy because it helps users anticipate the function of different elements.

Inherent vs. Learned Color Associations

Some color associations seem to be nearly universal. For example, red is often associated with passion, danger, or importance. In nature, it can signal ripeness in fruit or a warning from an animal. We use this association constantly in our daily lives. A stop sign is red. A warning light on your car’s dashboard is red. In interface design, using red for an error message or a “delete” confirmation leverages this learned association. The user does not need to read the text carefully to understand that this is a critical, and possibly destructive, action.

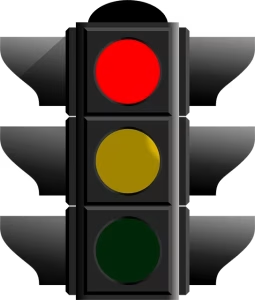

Similarly, green is widely associated with nature, stability, and “go.” A green traffic light tells us it is safe to proceed. In user interfaces, green is almost universally used for success messages. When you successfully submit a form and a green message appears, you instantly feel a sense of completion and correctness. Blue is often associated with trust, calm, and professionalism, which is why it is so prevalent in banking and corporate websites. By using these conventions, you are speaking a visual language that your users already understand. This makes your interface more intuitive and strengthens the visual hierarchy by attaching function and meaning to color.

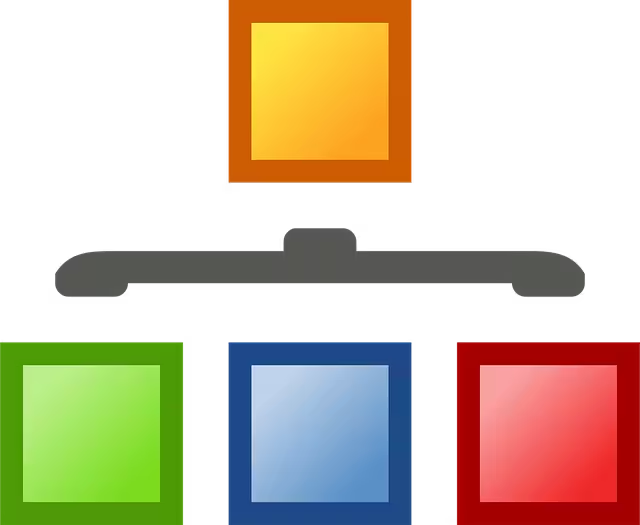

Creating a Functional Color System

To apply these principles consistently, you should establish a functional color system for any project. This means assigning specific jobs to specific colors, ensuring they are used the same way across the entire website or application. A consistent system creates a predictable visual hierarchy that users can learn and rely on.

- Interactive Elements: Choose a single, distinct accent color for all primary interactive elements. This includes links, main buttons, and selected menu items. Often, this will be a vibrant, saturated version of the brand’s main color. By using this color consistently, you teach users to recognize what is clickable. This creates a clear visual hierarchy of action.

- Informational States: Define a palette for system messages. This is where you use those powerful psychological associations.

- Success: A clear green for confirmation messages.

- Warning: An amber or orange for messages that require user attention but are not errors (e.g., “Your session is about to expire”).

- Error: A strong red for form validation errors or system failures.

- Information: A calm blue for helpful tips or neutral notifications.

- Text Hierarchy: This is where you put your luminance contrast rules into a system. Do not just choose text colors randomly. Define them.

- Primary Text: This is for your main body copy. It should have the highest contrast (e.g., a near-black like

#111111on a white background). - Secondary Text: For subheadings and metadata. This should have a slightly lower contrast (e.g., a dark gray like

#555555). - Tertiary/Disabled Text: For hints, placeholders, and inactive elements. This should have the lowest acceptable contrast (e.g., a lighter gray like

#999999).

- Primary Text: This is for your main body copy. It should have the highest contrast (e.g., a near-black like

By creating and sticking to this system, you ensure that your visual hierarchy is not only strong but also consistent and meaningful, making your design feel professional and intuitive.

4. Accessibility by Design: The Non-Negotiable Mandate

Creating a strong visual hierarchy is not just about creating a good experience for some users; it is about creating a usable experience for all users. This is where accessibility comes in. Accessibility is the practice of designing products so that people with disabilities, including visual impairments like color blindness, can use them. When it comes to font color, accessibility is not an optional extra. It is a fundamental requirement for any professional design. Ignoring it means you are excluding a significant portion of the population and failing to build a truly effective visual hierarchy.

Introduction to WCAG and Color Contrast Ratios

The most important standard in web accessibility is the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), developed by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). These are the international standards for how to make the web accessible. WCAG provides specific, testable criteria for design, and one of the most important is the requirement for minimum color contrast.

WCAG measures contrast as a ratio between the luminance of the text and its background. To make this simple, think of it as a score. The higher the score, the higher the contrast. WCAG sets two main levels of compliance:

- AA Standard: This is the most common target for accessibility. It requires a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 for normal-sized text and 3:1 for large text (which is typically 18pt/24px or 14pt/18.5px bold). This level ensures that your design is usable for many people with visual impairments.

- AAA Standard: This is a stricter standard, often required for websites focused on older audiences or those with a specific accessibility mandate. It requires a ratio of at least 7:1 for normal text and 4.5:1 for large text. This provides an even better experience and a more robust visual hierarchy for everyone.

Meeting these standards is not a matter of guesswork. There are many free online tools that allow you to check the contrast ratio of your chosen colors instantly. Using these tools should be a mandatory step in any design process. It is the only way to be sure your visual hierarchy is not breaking down for users with vision loss.

Why You Cannot Rely on Color Alone

A significant percentage of the population, especially men, has some form of color vision deficiency, commonly known as color blindness. The most common type makes it difficult to distinguish between red and green. If your design relies only on the difference between red and green to communicate something important, like an error state in a form field, it will be completely unusable for these individuals. Their ability to understand the visual hierarchy you have created will be lost.

This is why a core principle of accessible design is to never use color alone to convey information. You must always provide a secondary visual cue. For example:

- If a link is only identifiable by its blue color, users who cannot perceive that hue may not know it is clickable. Links should also have an underline.

- If an error field is only indicated by a red border, you should also add an icon (like an exclamation mark) and descriptive error text.

- Instead of just using color to show the selected item in a menu, you should also change the font weight to bold.

By pairing color with these other indicators, you ensure that your visual hierarchy is robust and can be understood by everyone, regardless of how they perceive color.

Essential Tools for Compliance

Integrating accessibility into your workflow is easier than ever thanks to a variety of excellent tools.

- WebAIM Contrast Checker: This is a simple, popular online tool where you can enter your text and background colors (in hex codes) and it will immediately tell you the contrast ratio and whether it passes WCAG AA and AAA standards.

- Adobe Color: Adobe’s powerful color tool has a built-in accessibility checker that allows you to test your entire palette at once, flagging any combinations that fail contrast requirements.

- Browser DevTools: Most modern browsers like Chrome and Firefox have accessibility features built into their developer tools, allowing you to inspect elements on a live webpage and check their contrast on the fly.

Using these tools is not a burden; it is a mark of professionalism. It ensures that the visual hierarchy you have so carefully constructed is effective for every single user.

5. Practical Application: A Strategic Framework for Your Palette

Theory is important, but the goal is to apply it effectively. Putting all these principles together-contrast, psychology, and accessibility-can feel overwhelming. Fortunately, there are simple frameworks and models you can use to guide your decisions and ensure you are building a consistent and effective visual hierarchy every time.

The 60-30-10 Rule in UI Typography

Originally a rule from interior design, the 60-30-10 rule is a wonderfully simple and effective way to create a balanced and hierarchical color palette for an interface. It provides a basic recipe for distributing your colors to create harmony and a clear visual hierarchy.

- 60% (Primary Text Color): About 60% of the text in your design should be your primary, most readable color. This is almost always a near-black or very dark gray. This color dominates the design and serves as the foundation for your content. It anchors the visual hierarchy.

- 30% (Secondary Text Color): About 30% of your text can be your secondary color. This is often used for your headings, subheadings, and other slightly less important text. This could be a slightly lighter gray or a muted, dark version of your main brand color. This color creates a clear second level in the visual hierarchy, distinguishing structure from content.

- 10% (Accent/Action Color): A small but vibrant 10% of your color usage should be reserved for your accent or action color. This is the star of the show. It is used for your most important elements: links, Call-to-Action buttons, and other interactive elements. Because it is used so sparingly, this color has immense power. It draws the eye and clearly tells the user what is most important to do. This is the top level of your action-oriented visual hierarchy.

Case Study: Analyzing a Well-Designed Website

Let’s look at a well-known example, like the website for the payment processor Stripe. Their design is a masterclass in clean, effective visual hierarchy. Notice how their main body text is a very dark gray (the 60%), making it extremely readable. Their headings are often a slightly bolder weight of the same color or a subtly different shade (the 30%).

But the most important elements-buttons like “Start now” or clickable navigation links-are rendered in a vibrant, saturated blue or a gradient (the 10%). This color is used nowhere else. This disciplined system creates an effortless visual hierarchy. Your eye is drawn to the headlines for structure and to the blue elements for action, all while the body content remains perfectly legible. They successfully built a powerful visual hierarchy by following these exact principles.

Conclusion: Color with Competence and Purpose

We have seen that font color is far more than a simple matter of taste. It is a precise and powerful design tool that, when wielded with knowledge, becomes the primary architect of a clear visual hierarchy. The effective use of color is a function of understanding its core components: luminance contrast is the king of readability and structure; color psychology provides a shortcut to meaning and function; and a commitment to accessibility ensures that the visual hierarchy you create works for every user. By moving beyond decoration and embracing color as a functional tool, you can create interfaces that are not just beautiful, but truly intuitive.

Effective color use is the difference between a design that feels chaotic and one that feels effortless. It is about making conscious, informed decisions that guide your users, reduce their cognitive load, and help them achieve their goals. The next time you begin a project, do not just choose colors that look good together. Choose colors that work together. Start by auditing your own projects with a contrast checker. This simple first step can begin your journey toward mastering color and building a more effective, accessible, and professional visual hierarchy in all of your work.